In this article, Martin Heide, Principal at NH Architecture, and Marcus Strang, Technical Lead (Passivhaus) at HIP V. HYPE explore the non-linear materials economy through projects that demonstrate strong leadership in applying circular economy principles.

Circular thinking is fast emerging as a critical consideration for design teams seeking genuinely regenerative outcomes. At its core, circularity challenges the prevailing ‘business as usual’ mindset that underpins the linear economy: where materials are mined, manufactured, used, and discarded. In contrast, a circular economy keeps resources in use for as long as possible, preserving their value and reducing environmental impact.

In the built environment, this means reusing entire buildings or components, remanufacturing materials, designing to prevent waste and material leakage, and maximising recycling.1 These strategies are reshaping how we conceive of architecture, construction, and material life cycles.

It’s encouraging to see the growing number of projects embracing circular principles to build a non-linear material economy that benefits both community and stakeholders. We are both members of the Living Future Institute of Australia Technical Working Group (LFIA TWG). We actively apply circular principles to our projects and through our work, hope to shift industry norms, expand the application of circular design, and advocate for broader systemic change.

Burwood Brickworks: The Project That Changed the Way We Think About Building Materials

It’s rare for a single project to fundamentally shift how we design and build, but Burwood Brickworks has done exactly that. For the team at NH Architecture, this project challenged our assumptions, shifted our practices, and proved that circular thinking can be applied at scale in commercial architecture.

Pursuing Living Building Challenge Petal Certification demanded deep research and inventive problem solving, particularly around the Materials Petal. The project prompted a rigorous re-evaluation of the environmental impact of every material specified.

One of the project’s most remarkable achievements was diverting 99% of construction waste from landfill. This was made possible by implementing tailored, stage-specific waste sorting systems onsite throughout the build. More than 80 individual construction products were salvaged, both from the Burwood Brickworks site itself, and from across Melbourne, including Speedpanel, plasterboard, formply, furniture, and light fittings. Salvaged timber alone was sourced from 25 different locations.

Our team wanted to use timber with Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) chain-of-custody (CoC) for the project, due to their rigorous forest management standards and protection of the environment and communities. However, limited availability of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified timber in Australia was a persistent challenge, which ultimately proved to be a blessing in disguise. In response, our team contacted every FSC-certified timber mill in the country to identify what was available and how it could be incorporated into the project. This constraint led us to shift our focus toward salvaged materials, turning a challenge into a unique opportunity. We ultimately incorporated over 90 reclaimed materials into the project, including hardwood, hardware, walls, flooring, and landscaping elements.

Of course, working with salvaged materials came with its own set of challenges. By nature, reclaimed elements vary in size, shape, and condition. The entire project team had to remain agile, adapting designs and construction methods as materials were sourced and assessed.

Challenges and Opportunities for Storytelling at Burwood Brickworks

Prioritising salvaged and repurposed materials allowed us to embed layers of history and storytelling into the fabric of Burwood Brickworks.The palette of materials at Burwood Brickworks: steel, timber, brick, and concrete, reflect the more recent, industrial history of the site. There are many stories embedded in these materials. For example, the timber walls of the stairwell leading to the second floor reveal some of the stories behind where the salvaged boards were sourced from. Much of the timber in the building was salvaged, some from a former Abbotsford garment factory and more from a car auction house.

Recycled bricks were sourced from all across Melbourne for the project, including some that were produced on the site when it operated as a brickworks more than half a century ago. They’re incorporated into the façade in a number of creative ways: on the southern façade they’re laid in sections to reveal the manufacturer’s mark. Another section of the same wall is inscribed with words, chosen by the community and painted onto the brickwork by Melbourne artist Lachlan Philps. The western façade tells another story. Crushed recycled brick has been blended with glass and poured into the in-situ concrete wall, producing a richly textured, tactile surface. Through these design choices, Burwood Brickworks becomes more than a high-performance building. It becomes a vessel for memory, identity and place, where materiality and storytelling are inseparably intertwined.

Beyond Burwood Brickworks: applying our knowledge to change our practice

Design teams generate a significant amount of knowledge throughout a project’s lifecycle. One of the biggest challenges in advancing more regenerative design practices is ensuring that this knowledge is captured and shared beyond the immediate project team.

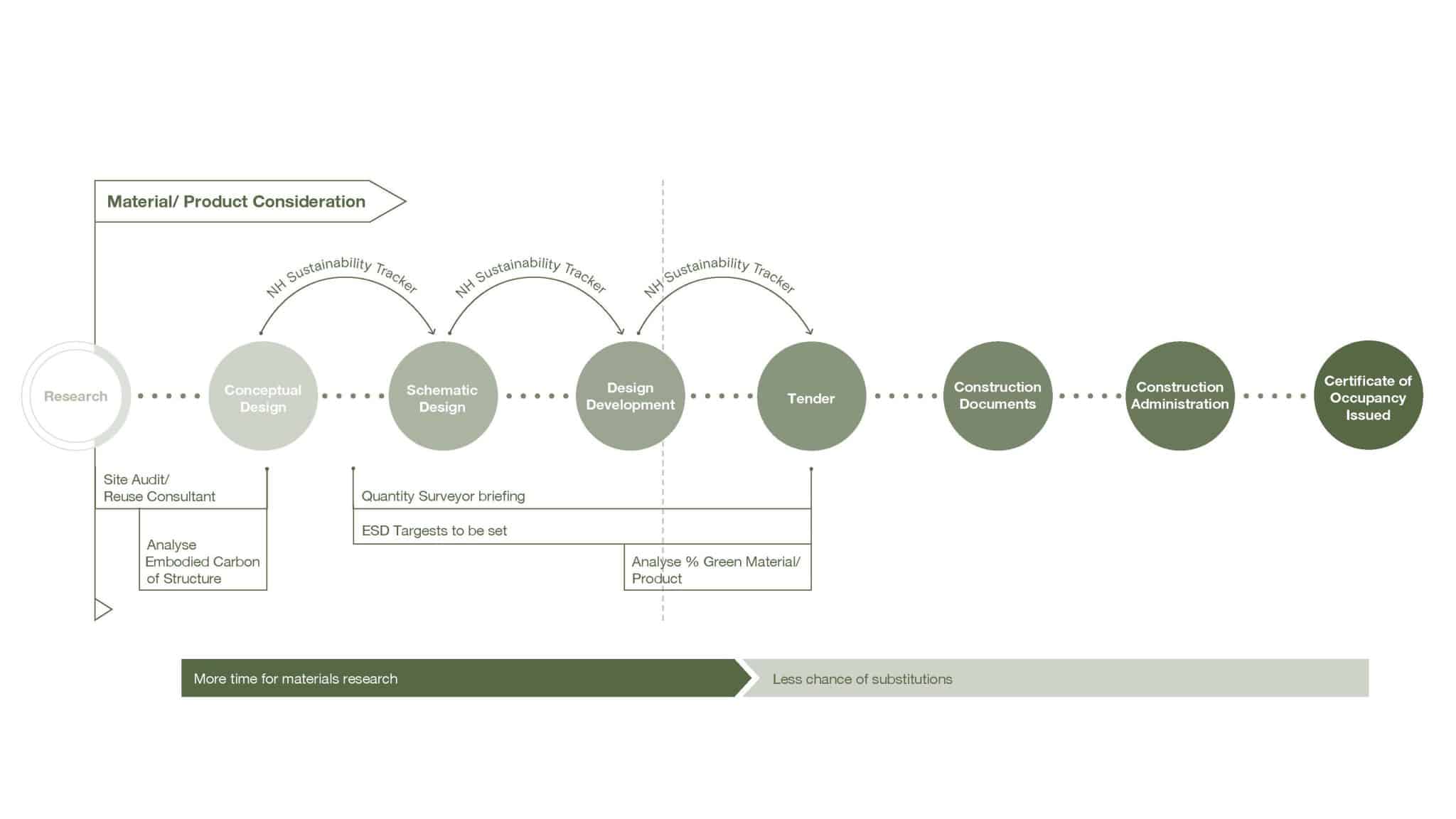

This is not as simple as it should be. Project environments are often insular, and timelines are tight, particularly on projects targeting ambitious sustainability frameworks like the Living Building Challenge. There is rarely time for reflection. At NH Architecture, we’ve recognised the importance of building systems that allow us to document and share what we’ve learned. Projects like Burwood Brickworks have shown us that to fully leverage the insights gained, we must intentionally create opportunities for cross-pollination within and across teams.

Each of these changes, however small, represents a step in the right direction. By embedding circular thinking into our standard ways of working, our teams can make more informed, values-driven decisions from the outset. More broadly, it signals a growing cultural shift within our practice – toward systems thinking, greater transparency, and a deeper accountability to environmental and human health.

The Bayside Repair Café: a community-led approach

The Bayside Roving Repair Program demonstrates strong leadership in advancing the circular economy by prioritising waste avoidance, resource recovery, and reduced landfill contributions. HIP V. HYPE were engaged by Bayside City Council to support the development of this initiative, which builds on the council’s broader commitment to helping the community transition toward a more circular way of living. The program complements existing local services such as the Toy Library and Men’s Sheds. These initiatives focus on sharing, borrowing, and repair, and the new program expands the reach and impact of these principles.

A core objective of the program is to move beyond the traditional linear take-make-waste model and foster greater community engagement around repair and reuse. This means encouraging collaboration across all levels of society, from local government to businesses and residents. As part of our engagement, HIP V. HYPE conducted a comprehensive desktop review, community surveys, and stakeholder interviews to inform the development of a business model for a Bayside-based repair service. The model was designed to maximise long-term value for the community, both environmentally and socially.

Since its launch, the program has helped spark a repair culture across the municipality. It offers residents opportunities to fix items that would otherwise be discarded, while also building local knowledge, skills, and social connection through a series of engaging community events. The initiative highlights how councils can take an active role in supporting circular practices that deliver both environmental and community benefits.

A council spokesperson said that a series of repair workshops, supported by volunteer repairers taught the community how to repair everything from textiles to electronics and even bicycles.2 The mobile repair events were hosted at different locations within Bayside. The project was very well received and won an award at the Waste Innovation and Recycling Awards in 2024.3

“We really wanted to promote a circular economy and it was a raging success. I’m really proud to accept this reward.” 4

However, challenges remain in the repair and reuse sector. Recent research by the Consumer Advocacy Group CHOICE highlights barriers such as high repair costs, lack of repair skills, and the convenience of replacement.5 Further complicating matters, product design often hinders repair efforts, with manufacturers using glued or sealed casings and locking software to prevent third-party repairs. Increasing the cost of parts further diminishes the financial viability of repairs. These challenges underscore the importance of thoughtful design and policy considerations when developing a local reuse and repair service. The Bayside Repair Café stands out as an early adopter in addressing these issues and supporting the shift toward a circular economy by providing practical solutions for repair, reuse, and resource recovery, paving the way for future community and council-driven sustainability efforts.

EnerPHit: The Passive House standard for retrofits

There is a critical need for the circular strategies of retrofitting and reuse of existing buildings, as 87% of today’s buildings will still be occupied in 2050.6 Therefore retrofits are becoming critical in how we decarbonise the built environment. The EnerPHit standard7 is a certification standard developed by the Passive House Institute for retrofitting existing buildings to achieve highly energy-efficient performance and comfort, while acknowledging the limitations and challenges of retrofitting, compared to new construction. It shares the same core principles with the Passive House standard, but with slightly less stringent metrics. As the saying goes, “if you do it, do it right!”. The EnerPHit standard follows this adage by retaining the original structure of the building, by preventing locked-in sub-optimal operational performance, while still achieving a high quality cost-effective solution. It does this by reducing energy demand for existing building stock, often achieving up to a 90% reduction in heating energy, compared to conventional buildings. The EnerPHit approach follows detailed climate-specific modelling, while the independent certification process ensures that the retrofitted buildings meet the modelled performance criteria through a rigorous quality assurance process.

HIP V. HYPE have worked on a number of certified EnerPHit projects in Australia as Passivhaus designers and Certifiers. One EnerPHit of note is a retrofit of a single-storey heritage-listed home in Coburg North, which combined the restoration of existing double-brick walls with the addition of an architecturally designed two-storey extension. Designed by Agius Scorpo Architects and built by Topp Constructs, the project achieved the clients’ goals for extensive reuse of materials from the original demolition. This included retaining the structure and the brick facade, bio-based durra panel insulation wall linings,8 recycled timber flooring, and responsibly sourced CERES Fair Wood9 Macrocarpa cladding, locally-made BINQ timber-framed windows.10 The project achieved the challenging EnerPHit certification,11 in addition to the Plus class,12 acknowledging the net-positive renewable energy generation of the project.

Supporting Circularity Through Policy and Practice

The economic and environmental value of circularity is increasingly recognised and supported at both Federal and State Government levels in Australia. The National Circular Economy Framework13 outlines a vision to double Australia’s circularity by 2035. This framework highlights the benefits of transitioning to an economy where waste is designed out, materials are continually cycled, and products are built to last—marking a profound shift across industries.

At the state level, the Victorian Government’s Circular Economy Plan14 sets out systemic changes needed for a cleaner, greener Victoria with less waste and pollution, more jobs, and a sustainable, thriving circular economy. Central to these strategies is connecting demand and supply markets to close the loop on materials.

However, circularity only succeeds when there is sufficient demand. Without it, the loop breaks. To scale circularity in construction, companies must specify circular products, architects need to design with regenerative materials in mind, and procurement teams must look beyond upfront costs.

Several companies are leading the way by offering circular products and services that projects can incorporate. Some best practice examples of these in Australia include:

- Five Mile Radius is a cross-disciplinary design and fabrication studio that makes heavy use of local salvaged, low-carbon and bio-based materials, skills, and stories.

- Assembly Systems explores the use of novel modular timber-framed building systems to scale-up high-performance homes that can be adaptively reused and relocated. See further information here (16).

- Circuiti produces circular solutions to eliminate waste by networking circular businesses together retaining value in corporations.

- Crafted Hardwoods uses underutilised low-grade and juvenile hardwood materials, manufacturing them into premium hardwood products to maximise yield and reduce waste.

- Paintback diverts unwanted paint and packaging out of landfill, treated, and returned into new paint products.

- Planet Protector provides sheep wool insulation, recycled denim fibre insulation, and recycled polyester from waste streams.

- Repurpose It converts construction, demolition and excavation waste into in-spec sand and aggregate products.

- Revert Group provides circular economy solutions that extend inventory and material life cycles for commercial and refurbishment projects.

- Revival Projects store, structural certify, and repurpose construction and demolition waste from landfill, especially structural timbers, to be more accessible to architects, designers, builders, and manufacturers.

- saveBOARD is a low-carbon building material made from upcycled packaging.

- Upparel collects clothing, shoes, and textiles to divert them from landfills, recycling them into insulation, furniture filling, packaging and signage.

We strongly encourage designers, engineers, developers, clients, and policymakers to embed circular strategies and products into their projects and push for supportive legislation that enables more ambitious approaches. This includes increasing demand for circular products through strong client commitment, embedding material recovery and circularity targets into project contracts, and delivering demonstration projects that showcase practical, tangible outcomes. By clearly communicating the successes of these efforts, we can build greater momentum for change and inspire others to follow suit.

The more we can share our learnings and advocate for change, be it within our studios, with our clients, and across the broader industry, the greater the impact we can collectively achieve. Through collaboration, leadership, and action, we can unlock the potential of circular design and lead the transformation toward a more sustainable and resilient built environment.

Credits:

Burwood Brickworks shopping centre 2019 by NH Architecture, interiors by Russell & George in collaboration with NH Architecture, ceiling mural and façade artwork by Mandy Nicholson. Image credits: Peter Bennetts and Peter Marko

Bayside City Council engaged HIP V. HYPE to conduct a feasibility study in 2020 to collate evidence on the best model for a repair and re-use centre, and the appetite for a repair café within Bayside and what that would look like. This led to the council creating the Bayside roving Repair Program. Image credits: Bayside City Council

The Coburg North EnerPHit house 2023 was designed by Agius Scorpo Architects, while HIP V. HYPE acted as the Certified Passivhaus Designer, and Detail Green as the Passivhaus Certifier. Image credits: Thurston Empson

References:

(1) Arup. Circular Building Toolkit. https://ce-toolkit.dhub.arup.com/strategies (accessed 10.10.25).

(2) Bayside City Council. Bayside Roving Repair Program. https://www.bayside.vic.gov.au/services/waste-and-recycling/roving-repair (accessed 17.3.25).

(3) Pittorino. 2025. Bayside City Council sets an example at Waste Innovation and Recycling Awards. https://wastemanagementreview.com.au/bayside-city-council-sets-an-example-at-waste-innovation-and-recycling-awards/ (accessed 26.9.25).

(4) Pittorino. 2025. Waste awards highlight excellence. https://wastemanagementreview.com.au/waste-awards-highlight-excellence/ (accessed 26.9.25).

(5) Australians push for stronger protections and repair rights for household products, 2021, https://www.choice.com.au/shopping/consumer-rights-and-advice/your-rights/articles/stronger-protections-and-repair-rights-for-household-products (accessed 4.4.25)

(6) Arup. Building retrofit. https://www.arup.com/en-us/services/building-retrofit/#:~:text=Given%20that%2087%25%20of%20today’s,and%20thousands%20of%20reuse%20projects. (accessed 20.7.25)

(7) Passipedia. 2025. EnerPHit: The Passive House Standard for retrofits. https://passipedia.org/certification/enerphit (accessed 20.7.25)

(8) Durra Panel. https://durrapanel.com/the-product/ (accessed 20.7.25)

(9) CERES Fair Wood. 2025. https://ceresfairwood.org.au/?srsltid=AfmBOopsXuP6vdDrnDafyN5yso1-TNt5_3UptOo-zQJKGYkayCUDj-bF (accessed 20.7.25)

(10) BINQ windows. https://www.binq.com.au/ (accessed 20.7.25)

(11) Passive House Database. https://passivehouse-database.org/index.php?lang=en#d_7859 (accessed 20.7.25)

(12) Passipedia. 2024. The Passive House Classes: Classic, Plus and Premium. https://passipedia.org/certification/passive_house_categories (accessed 20.7.25)

(13) Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. 2024. Australia’s Circular Economy Framework: Doubling our circularity rate. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australias-circular-economy-framework.pdf (accessed 20.7.25).

(14) The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. 2020. Recycling Victoria: A New Economy. https://www.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-03/02032020%20Circular%20Economy%20Policy%20-%20Final%20policy%20-%20Word%20Accessible%20version%20.pdf (accessed 20.7.25).

(15) Yan, Z., Strang, M., Ottenhaus, L., Leardini, P., Adams, P., and Crews, K., 2025, Implementation of Adaptable Design Principals for High-performance Light Timber Framed Panelised Buildings: An Australian Case Study. Conference: World Conference on Timber Engineering 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392616621_IMPLEMENTATION_OF_ADAPTABLE_DESIGN_PRINCIPLES_FOR_HIGH-PERFORMANCE_LIGHT_TIMBER_FRAMED_PANELISED_BUILDINGS_AN_AUSTRALIAN_CASE_STUDY (accessed 10.10.25).